My second visit to Bilibid Prison was under very different circumstances. In fact the day following my second visit one of the Manila papers referred to it under a typical tabloid headline: “Balloons and Bibingka for Benjamin’s Birthday.”

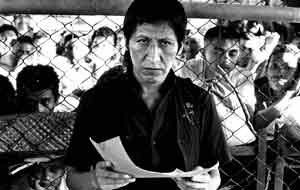

My friendship with the Bolivian surreal artist, Benjamin Mendoza, began in 1969. By that time I considered myself an old Manila hand, regarded by many locals as an honorary Filipina and by the Indios Bravos crowd a resident fixture of the cafe. Benjamin Mendoza was the new guy in town. As with most newcomers, particularly artists, it did not take long for him to gravitate towards the welcoming crowd in Indios Bravos. I met him on his first visit to the coffee shop. He was sitting alone and I instantly recognized him as a South American. He had the dark, elongated face, the fine aquiline nose and the thin lips, all familiar facial characteristics of the Quechua peoples of the Andes. I introduced myself and joined him at his table.

I was curious to find out why he had come to Manila, what had brought him there? “The art!” he told me, “I read books and magazines. I read about the vibrant art scene in Manila. I wanted to see it for myself. After all, Latin America and the Philippines have a common background – Spanish conquistadores and Roman Catholic priests. I wanted to see if our art was similar too.” He pulled out some small paintings from his battered briefcase and passed them across the table to me. They were miniature oil paintings, mainly of animals and religious subjects, in dark, brooding tones, the only light emanating from them were painted shards of broken glass around the edges. “What do they say to you?” he asked as I tried to look like I was studying them seriously.

I was tempted to say I had no idea but I was certain a psychiatrist would have found them challenging. But not wanting to appear inpolite, I smiled. “They’re good. I like them. What did you want me to see in them?”

“Vignettes of life. Hope, despair. Good, bad. Love, hate. Anger, serenity. Life is made up of contrasts. You can’t have one without the other.” He looked at me sideways as he stabbed a toothpick into the fried spring roll on his plate. “Haven’t you ever ended up hating someone you really loved? Had moments of immense happiness that resulted in tears? Had instances of unparalleled pleasure that turned into pain? That’s what I’m trying to say in my paintings.”

His voice was hushed, barely audible. Not because of the background music, “Hey Jude” by the Beatles playing loudly from the café’s sound system but simply because that was the way he spoke. Benjamin was gentle, thoughtful, if slightly morose.

Over the following months we forged a friendship of sorts. But whereas Benjamin was a solitary person, I was the opposite. He joined the Manila artists’ group, participating in their weekly gatherings but at the same time remaining on the periphery, belonging but apart. Many found him aloof, slightly weird but harmless. Betsy and I enjoyed his company and he soon became yet another regular in the cast of characters unique to the Indios Bravos cafe.

One evening Benjamin and I were sitting at his table discussing religion, one of his favourite topics.

“You’re so lucky, Caroline,” he mused, “you weren’t brought up in fear. You weren’t forced to accept something you didn’t believe in. You weren’t punished for rejecting God. You weren’t threatened for questioning the Church’s motives. You didn’t feel you were sinning when you took precautions….birth control, I mean.”

“I’d hate to imagine where I’d be without the Pill!” I joked, “It would have cramped my style considerably. I’d probably have given birth to a complete basketball team by now!” I was making light of the discussion because I noticed the rising intensity in his voice.

“Exactly. But in my country and in all poor Catholic countries women die – here too, probably – because they are expected to go on and on having children. Just to keep the Church happy.”

I felt his anger. I reached across the table to touch his hand, attempting to mollify him.

“I’d be angry too, you know.”

I was grateful at that moment that the only Catholics in my family, my mother and my sister, had never tried to convert me.

Benjamin stared into his glass without saying a word. I could sense he was fighting back the overwhelming urge to share his anger with everyone in Los Indios Bravos that night. But, whatever lies were to be written about him some months later, Benjamin was quiet, mild-mannered and reserved, a person who would never consider upsetting the mood of the evening.

But on the morning of the 27 November 1970 that impression of him was about to change dramatically or, at least, called into question. I was back in London watching the world news on television.

Curiously enough there were several firsts that day. In London the first Gay Rights demonstration, a candlelight vigil against police harassment, was taking place in Highbury Fields.

“A milestone in gay history,” said Peter Tatchell, one of the 150 participants. “Today instead of fear we feel pride and defiance!”

In Plesetsk, Siberia the communications satellite Molniya 8 was launched successfully into orbit. This was followed by the news of a plane crash in Anchorage, Alaska. A Capitol Airways DC 8, flight number 472, crashed on take-off, killing 48 and injuring 226.

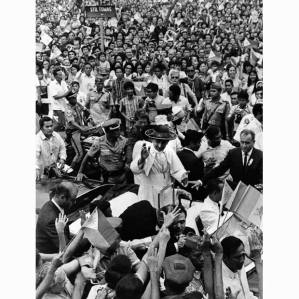

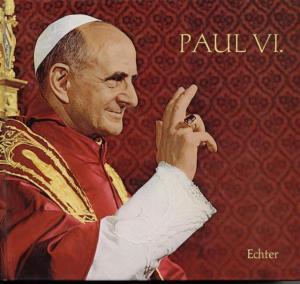

And in Manila 180 Bishops had convened for the first ever Pan-Aseatic Bishop’s Conference. They were shown at the Manila International Airport waiting for the arrival of Giovanni Battista Montini, Pope Paul VI. And, despite the Philippines 400 years of Spanish Catholic colonization, Montini was the first Pontiff ever to set foot on Philippine soil.

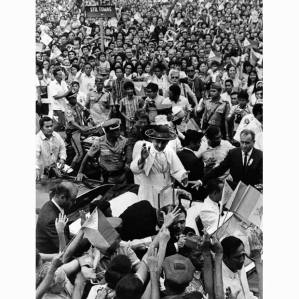

Leading up to his visit there had been much speculation in the local and international Press as to whose guest the Holy Father would be – the Catholic Church or Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. For the only predominantly Catholic country in Asia, this visit was considered to be a momentous occasion and the kudos to be gained, both politically and commercially, from having the Pope stay in Malacanang Palace was immeasurable. Marcos hoped it would be viewed among the population as an endorsement of his increasingly dictatorial rule. In the months leading up to the Papal visit the value of the peso had plunged, food was in short supply and jobs were scarce. Civil disorder, student demonstrations and organized rallies had become commonplace. These confrontations had been met by violent, sometimes bloody, resistance by Marcos, his constabulary and his armed forces. Marcos was more unpopular now than he had ever been and he blamed many in the priesthood for fomenting political unrest among the students. Here was an opportunity to demonstrate to his predominantly Catholic nation and to the world that he had the full approval and support of the Vatican. Both Ferdinand and Imelda were determined to exploit the event to the full. But neither had counted on the formidable personality of Cardinal Santos, whose increasingly vocal opposition to the Marcos regime now turned into open warfare. His stand against the Marcoses on this point was very public, vociferous and humiliating. He stuck his ground, declaring this was purely a pastoral visit by His Holiness to address his flock and to attend the Bishops’ Conference. He went further, the Holy Father would not be staying at the Palace nor would he be driven from the airport into the city in the Presidential limousine. Fuming, the First Lady, too, refused to give way, insisting she had extended a personal invitation to the Pope during her visit to the Vatican the previous year.

The heated battle of the two adversaries was still deadlocked on the day of the Pope’s arrival. Whether His Holiness knew of it or not, separate itineraries had been prepared for him by both his Cardinal and the First Lady. But it was all deference, bell-pealing, flag waving and smiles as the frail seventy-year old Pontiff stepped off his Alitalia plane at Manila International Airport.

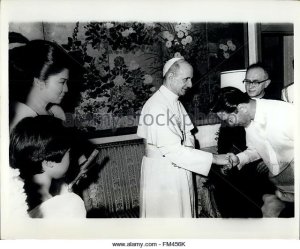

Waving to the crowd, the Pope stooped for a moment to accept a bouquet of white flowers from Irene, the Marcos’s youngest daughter. He shook hands with the President and First Lady and began to cross the red carpet towards the dais. The crowds roared their welcome and pitched forward upsetting the barriers, hoping to get closer to their Pontiff. Under strict instructions from Cardinal Sin the Catholic hierarchy moved in immediately to flank and protect the diminutive figure of Paul VI.

One by one the Cardinals and Bishops bowed down to kiss the Pope’s ring. The Marcoses, who planned to demonstrate their closeness to His Holiness in front the world’s TV cameras and the masses of Filipinos who had assembled at the airport to witness this historic occasion, had to be content to walk behind the Pope. I watched the news report live as Paul VI slowly made his way along the red carpet towards the dais, stopping to shake hands with all the dignitaries lining his route.

Among the many faces I recognized, the politicians, the journalists and the clergy, there was one face that made me sit up and take notice. No, I thought, it can’t be, I must be mistaken. I peered closer hoping for a better look. And there he was. With his hand outstretched towards the approaching Pontiff and dressed in a long, black priestly sutane, the person I saw was my erstwhile friend, the Bolivian artist, Benjamin Mendoza.  It couldn’t be. Why on earth would he be there? How did he get past security? Was I just imagining things? Or was it one of his surrealist jokes?

It couldn’t be. Why on earth would he be there? How did he get past security? Was I just imagining things? Or was it one of his surrealist jokes?

I tried to convince myself that Mendoza must have been on my mind because I had just received a postcard from him a few days earlier saying he was planning to return to Bolivia. So perhaps this man, whoever he was, was simply an Andean priest, part of the Vatican’s entourage. I continued to scan the screen but the image I was searching for was obscured.

Suddenly there was pandemonium, a glint of steel, screams, shouts, gasps and lunging, writhing bodies scrambling to the ground. I had no idea at that moment what had happened. An hysterical voice on the news report informed us an attempt had been made on the Pontiff’s life by an unknown assailant armed with a knife. Silence. Then we were told that, mercifully, the Pope was safe. The assailant had been overcome by Papal security guards. This last piece of information was vital considering the story put out less than twenty-four hours later by President Marcos.

Several times that day I watched for further news to learn the identity of the assassin. Finally I was both rewarded and shocked to learn that the would-be killer was none other than a Bolivian painter by the name of Benjamin Mendoza y Amor. I was stunned. Even more extraordinary was Imelda’s revelation that she had witnessed her husband saving the Pope’s life by delivering a karate chop and a flying kick to the would-be assassin, knocking the 10-inch knife right out of his hand at the crucial moment.

There must be some mistake, I thought. I knew Benjamin disapproved of the Catholic Church but he would never have gone this far, I could have sworn it. It must have been a practical joke gone very wrong or, more likely, a scenario dreamed up by the Marcoses to upstage the Cardinal. The next day film footage was released showing Benjamin Mendoza attending a very obviously rehearsed press conference at the Philippine Constabulary Headquarters at Camp Crame. He was being grilled by members of NBI, the Philippine’s National Bureau of Investigation and the Philippine Armed Forces.

In an uncharacteristically animated voice Benjamin said, “I feel disappointed for failing to kill the Pope and would do it again if given another chance.”

The NBI Director leaned towards the artist and asked, “And who saved the Pope’s life?”

“I had thought it was President Marcos,” Benjamin dutifully replied, intently looking at his interrogator and sounding well-coached, “but I wasn’t too sure. But then when I saw the pictures you showed me, I am convinced it was really the President who prevented me killing the Pope.”

In fact the photos that were published showed the President far too distant from both the Pope and the artist to have either saved the one or delivered a crippling karate chop to the other.

Members of the Catholic Church who had surrounded the Pontiff at the time all agreed with the Bishop of Sarawak who, on his return to Indonesia some days later, stated categorically, “I was very close to His Holiness at that moment and I do not remember seeing President Marcos give the Bolivian painter a karate chop and a kick.” He went on to say, “It was one of the two papal security guards who played the vital role of saving the Pope for it was he who stuck out his hand to parry the attacker’s lunge and pushed His Holiness away – right into my arms. I held him tight, pulling him away until the security men grabbed the assailant and dragged him away.”

Despite the credible rebuttal the filmed interview with Benjamin Mendoza at Camp Crame was replayed all week on Philippine television. For the time being, it seemed, in the eyes of the majority of Filipinos, President Marcos was presenting himself as the hero of the hour. Since Benjamin Mendoza had played right into the President’s hands, he was treated leniently. He was sentenced to four years in Bilibid Prison and deportation upon his release.

When I returned to Manila in 1972 I got in touch with him. Because of my previous visit to Bilibid I was allowed to speak directly to him without going through the authorities. Benjamin sounded content. He told me he was well looked after but that he was looking forward to returning to his family in Bolivia.

“It was a surrealist gesture, Caroline,” he told me, answering my unspoken question. “I had no intention of killing him.”

“And Marcos,” I asked, “where did he come into it?”

“Now that’s a question you know I can’t answer,” Benjamin chuckled. “You’ll get yourself into trouble if you ask me such things and I’ll get into trouble if I tell you.” Abruptly he changed the subject. “When will I see you? Will you visit me?”

“Of course,” I answered, “when?”

“Well, next Sunday’s my birthday. I’m thirty-seven. Why not come then?”

“It’s a date,” I said, “and I’ll get the Indios Bravos group to come along too.” I replaced the receiver and immediately started planning. Betsy and Henry jumped at the opportunity. The dancer Delia Javier agreed to come too. Ben and a few of the other artists, writers and poets were ready to join in the fun. Together we assembled gifts galore, hampers full of picnic food and a birthday cake with thirty-seven candles. In the early afternoon we started out from Indios Bravos towards Bilibid in a convoy of jeepneys festooned with coloured balloons and streamers announcing “Happy Birthday Benjamin”. People in the street watched in amazement as we passed by, horns blaring and tapes blasting out loud music.

My feelings were mixed when I approached the gates. There would be many new faces but few of the old familiar ones. It was only three years later but Pancho had been released and Jaime, Dominador, Adriano and Mariano had been executed.

Security at the prison that day was lax. Everyone, officers, prisoners and guards, were all determined to have a good time. It was odd seeing Benjamin in his ill-fitting orange prison overalls. It was strange to see him squatting on the ground outside his cell and not sitting at his habitual table at Los Indios Bravos.

We spread the picnic around him and called all the guards and prisoners within hearing distance to join us. We lit the candles and methodically Benjamin blew them out, screwing up his eyes and making a wish as he did so. Everyone immediately burst into song. I found it ironic that here they all were singing Happy Birthday to possibly the most hated the man in the Philippines, the man who had almost succeeded in assassinating their beloved Pope.

Benjamin must have noticed my astonished look. He leaned over and whispered in my ear, “Yes, and there are a lot of born-again Christians in here too. Funny, isn’t it?”

I laughed. “Do they give you a hard time?” I asked, concerned that religious fanatics might single him out for harsh treatment.

“No. They love me,” he smiled, “I’m a celebrity, remember. And more than God they love celebrities in the Philippines, you know that, Caroline!”

It was true, of course. I should have known. Imelda had known it too from the beginning of the Marcos presidency. And she had exploited the cult of celebrity to the hilt. “Escapism for the masses” she called it. “It gives them something to brighten up their dreary little lives!” She also discovered it was a useful tool to smokescreen a multitude of sins carried out by the Marcoses, their government, their relatives and their cronies.

It was a memorable day but it was sad as I realized it would probably be the last time I would see Benjamin Mendoza. Soon after our visit he completed his sentence and was driven straight to the airport to board a plane back to Bolivia. I received one more postcard from him and then silence. I never knew how he was received back home, as celebrity, as prodigal son or as religious enemy.

I often wondered about it. And as to my unspoken questions, “Did Ferdie or Imelda organize the whole episode to win the hearts and minds of the Filipino people in her war with Cardinal Santos?”

Possibly. And if so, “why would Benjamin have agreed to it? Money?” I didn’t think so. “Notoriety?” I doubted it. Or simply, as he said, “as a surrealist gesture against the Church’s policy in impoverished countries such as Bolivia and the Philippines?”

In my opinion, that was far more likely. But whatever the reasons only Benjamin Mendoza knew them and he was keeping them to himself. For me, I would put my money on the Marcoses. They certainly proved themselves capable of staging a murder at Manila International Airport. Eleven years later, on 21 August 1983, in the full glare of the world’s TV cameras, the Philippines’ prodigal son, Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino, was making his triumphant return from exile in the United States when, as he stepped out of the plane, he was shot down in a hail of bullets, his body left sprawled on the tarmac.

Pope Paul VI’s visit to Manila in 1970 was at the time of Cardinal Rufino Santos who lived on until the time of his death in 1978. Only at the time of Cardinal Santos’ death was Bishop Sin appointed cardinal to take over Cardinal Santos’ post.

Thank you. I accept that I was, of course, confusing it with the second Papal visit, when Sin was already a Cardinal and he and Imelda had a fierce battle as to who would act as the Papal host.

Reblogged this on Caroline Kennedy: My Travels and commented:

This is the story of how I met Benjamin Mendoza, the Bolivian painter accused of attempting to assassinate Pope Paul VI on his pastoral visit to the Philippines.

Mendoza was still alive in 2009, and living in Lima — apparently in poor health. Here’s a review of a show he had in 2009: http://www.limagris.com/benjamin-mendoza-y-amor/. A friend of mine translated the videos for me. The gist of this is that the show was a benefit for him, as he was in delicate health. He had apparently been living in Peru for the last 20 years. He was characterized by the curator of the show as an acid critic of Society, its politics, religion and economics, showing the masks by which we are manipulated. No mention was made of his past. An artist commented that his art was first and foremost political, but the plasticity of his work kept it from getting stale.

That’s fascinating, Tim, thank you so much for this update. I often wondered, of course, what happened to him. I received a postcard from him a couple of years after he was deported from Manila. It was postmarked Peru but had no return address so I couldn’t reply. Sadly, I never heard from him again.

Hi Caroline,

I am Jerome Gomez, a writer for Esquire in the Philippines. I really enjoyed this piece. I am currently writing a piece on Mendoza (another Pope is visiting Manila this January) and hope you don’t mind if I quote some parts of your account of your friendship.

No problem, as long as you attribute your quotes to me. I would love to see your piece when it is published. Could you send me a link to it, please?

Thanks

Caroline

I will. Thank you very much.

Good Day, Ms. Kennedy!

This is Cheng Bigay from the Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office (PCDSPO) of the Philippines. The PCDSPO is mandated to act as custodian of the institutional memory of the Office of the President, which includes the supervision and control of the Presidential Museum and Library.

In regard to this, we are asking your permission if we can use your photo [https://anywhereiwander.files.wordpress.com/2010/01/pope-paul-arriving-manila1.jpg] for our briefer for the Papal Visit on 2015.

We would feature your photos on the official website of the Presidential Museum and Library [URL:www.malacanang.gov.ph] and, also, on our official social media sites, namely Facebook [URL:www.facebook.com/malacanang] Twitter [URL:www.twitter.com/govph] and Flickr [URL:www.flickr.com/govph]

Rest assured that your institution will be properly credited. Should you have any questions, please feel free to contact me through email at cheng.bigay@pcdspo.gov.ph

Thank you and we look forward to your prompt and positive response.

Sure, no problem. Thank you for requesting permission.

Hello,

I am an amateur artist/art collector and I have been trying to do research on a very special painting I bought several years ago. This may be a long shot, but I believe I have an original oil painting of Benjamin Mendoza and I have no idea where to start in the process of having it authenticated. I was wondering if you had any interest in looking at a picture of it, perhaps you can shed some knowledge on it. I haven’t been able to find more than a handful of samples of his artwork, and none have been oil paintings.

Thank you in advance.

How fascinating, Tiffany. I am not sure how much I could help you. But if you’d like to send me a photo, please do. My comments on it would not be those of an expert, just be warned!

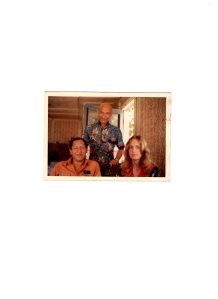

My family knew Benjamin in Hawaii around 1965-68; we used to go to his studio for dinner and he’d come to our house. My father visited him when he moved to Japan and the Philippines. I was always told that the knife Benjamin used was actually covered in tinfoil and had a ball at the end of it; it was just a symbolic gesture. Benjamin artwork (which we have many of) contained many symbolic images.

Thank you for this, Molly. What a fascinating story. Wish I had been able to speak to you before I wrote my article many years ago. Very nice to know he had some friends as he appeared quite a lonely figure in the Philippines. That’s probably why I befriended him in the first place. Please feel free to share more anecdotes if you have them. I would love to hear more. Thank you again.